Media inquiries contact:

Jessica Spatafore, Director of Development & Communications at (304) 413-0945 or email jessica@wvlandtrust.org

Adam Webster, Conservation & Communications Coordinator at (304) 413-0945 or email adam@wvlandtrust.org

New West Virginia Land Trust preserve a Mammoth undertaking

Charleston Gazette

By Rick Steelhammer

September 19, 2020

A 5,000-acre expanse of woodland and former surface mines along the Kanawha-Fayette County line east of Mammoth is being repurposed as a public recreation area and a demonstration site for post-mining reforestation and stream restoration by its new owner, the West Virginia Land Trust.

Mountain bike and hiking trails are among recreational amenities initially planned for the property, with the first trails likely to take shape in the un-mined segments that make up about half of the tract, named the Mammoth Preserve.

“It’s not wilderness, but it looks pretty wild,” said Ashton Berdine, lands program director for the West Virginia Land Trust, as he took in a miles-long view of wooded ridges and hilltops from one of the new preserve’s highest ridges. At the bottom of a narrow valley between the steep, tree-cloaked spines, the path of Hughes Fork could be seen twisting its way toward the Gauley River, along with the grassy slopes of re-contoured highwalls and mine benches.

“We will be managing this preserve for wildlife habitat, water protection and recreation access,” Berdine said.

“Mountain biking is only going to grow, and here we have room for maybe 50 or more miles of trail,” Berdine said. Trails for hiking are also planned, and paths for horseback riding and sites for camping will likely be considered, he said.

“The preserve also gets us involved with restoration,” he said. “We’re proud to be a part of the restoration of this land and having the opportunity to make it available to the public for recreation and to benefit the local economy.”

The West Virginia Land Trust was given the land and its management responsibilities by another nonprofit, Appalachian Headwaters. Appalachian Headwaters received the tract to use as a demonstration project for reforestation and stream restoration techniques as part of a settlement agreement in a stream pollution lawsuit against Alpha Natural Resources. The suit was filed by the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and the state chapter of the Sierra Club, represented by attorneys from Appalachian Mountain Advocates.

Appalachian Headwaters, based in Lewisburg, was formed four years ago to support reforestation of native hardwood forests and restoration of streams on former surface mines. It is working with scientists at Green Forests Work in Lexington, Kentucky, to plan the mix of trees to be planted on mine lands at the Mammoth Preserve.

“The goal is to return the mined land to the closest possible approximation of the forest that was here before the mining took place,” said Mike Becher of Appalachian Headwaters.

Once the blend of nursery-raised young trees is in the ground and growing on about 2,000 acres of former mine land in the preserve, it will be one of the largest, if not the largest, legacy mining reforestation site in Appalachia, according to scientists at Green Forests Work.

Preparation work for reforestation is already underway on about 300 acres of the preserve, where thickets of non-native autumn olive and Russian olive have been dozed into large piles, where they await burning. The two brushy plants do well in rocky, compacted soil, sometimes reaching heights of 20 feet or more, which is why they have been used extensively in the region to satisfy post-mining ground cover requirements.

The preserve lies adjacent to the remnants of Bullpush Mountain, the nation’s first mountaintop removal mine site, which Cannelton Coal began operating in 1970. Most of the mining that took place on the preserve also occurred decades ago, according to Becher.

“Past mine restoration throughout Appalachia often focused on getting anything to grow on these mine sites,” according to Berdine. The two olive species, both native to Asia, have frequently been planted on reclaimed strip mines, along with black locust, pine and certain hardy grasses and legumes, to help anchor the soil.

Where thickets of autumn and Russian olives have been scraped off old reclamation jobs at the Mammoth Preserve, dozers pulling giant, hydraulic “ripper” spikes tear up compacted soil to accommodate the successful planting of young hardwoods. The ripping is done in a crisscross pattern, at least three feet deep into the hardened soil.

“To get trees to grow in the compacted ground, you have at the Mammoth Preserve and other mine sites that were reclaimed as grasslands in the ’80s, you have to rip up the soil,” said Chris Barton, a professor of forest hydrology and watershed management at the University of Kentucky. “Ripping allows the natural infiltration of water to occur again,” he said. “It gives young trees the water they need for growth, and allows seeds from native plants to germinate.”

Without ripping and reforestation with native tree species, former mine sites like the Mammoth Preserve remain in “a state of arrested succession,” said Barton, who founded the non-profit Green Forests Work to help owners of former surface mines plan reforestation. “Our goal is to speed up the natural process,” he said.

Starting in March or early April, young trees will be planted in the land now being processed for reforestation. “We try to mimic the native forest with a blend of 20 to 30 species of trees and native shrubs found in an oak-hickory forest like the one at the Mammoth Preserve,” Barton said.

The return of a natural hardwood forest canopy above the former mine land will also improve water quality in streams crossing the new preserve.

Leaves in the canopy can absorb large volumes of rainwater while dissipating rainfall before it reaches the soil, Barton said, “and trees are deep-rooted and use a lot of water. That means less runoff and less erosion.”

“There are five or six guys operating heavy equipment here now, and later a dozen or so tree planters will be hired,” said Becher, as he watched a dozer with a ripper bar slowly ascending a small slope. “That’s the start of the sustainable economic activity that we’re wanting to make possible on this site. We want to do good for the environment while creating economic benefits for the community.”

“In the long term, we’ll be working with the local towns and county government to find out what they would like to see happening with the preserve and how we can draw more people to the Upper Kanawha Valley,” said Berdine.

Trail development at the Mammoth Preserve “ties into a local initiative Montgomery and Smithers have for new trails on both sides of the Kanawha,” said Smithers Mayor Anne Cavalier, who visited the preserve with West Virginia Land Trust officials on Monday.

“This would be another place to hike and bike you can reach without having to drive for hours,” she said, and maybe stop in Smithers or Montgomery afterward to get a bite to eat. “The best industry to support new development is the tourism industry.”

The preserve stretches from Hughes Creek, a Kanawha River tributary, in the west to a point within one mile of the Nicholas County line in the east near the town of Dixie. Bells Creek forms much of its northern boundary. All but a 400-acre arm of the preserve that extends into Fayette County in the Mount Olive area lies in Kanawha County.

In addition to the Mammoth Preserve, the West Virginia Land Trust has protected more than 10,000 acres of land in the state, including seven public preserves, since it was created in 1994.

Original story: https://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/new-west-virginia-land-trust-preserve-a-mammoth-undertaking/article_f1e21305-a027-5074-b898-775a99c87743.html

Effort underway to preserve Revolutionary War-era fort site in Greenbrier County

Charleston Gazette-Mail

By Rick Steelhammer

Jul 11, 2020

ALDERSON — A crowdfunding campaign is underway to protect the site of one of the strongest in a series of frontier forts built to protect colonial settlers in the Greenbrier Valley from raids by American Indians before and during the Revolutionary War.

The Archaeological Conservancy, the West Virginia Land Trust and the Greenbrier Historical Society are seeking to raise $125,000 — $60,000 of it from the crowdsourcing effort — to buy the fort site and a 25-acre parcel of land surrounding it. The three groups would then work together to create a public historical preserve, with signs, trails and exhibits pointing out the cultural and natural points of interest being protected from development.

The Outdoor Heritage Conservation Fund has committed $25,000 to manage the preserve.

While the location of the fort was known, no written description of it is known to exist, and no trace of the fortification could be seen above the surface of the pasture that covers it. Much of what is known about the structure and the activities that took place inside it was uncovered during a series of excavations conducted in the 1990s by archaeologists Stephen and Kim McBride.

The McBrides, both Greenbrier County natives with doctorates in archaeology, were assisted by students from public schools in Greenbrier County, students from the University of Kentucky, Concord and West Virginia University, and local volunteers.

Arbuckle’s Fort was built in 1774 by a local militia company commanded by Captain Matthew Arbuckle on a knoll overlooking the point where Mill Creek flows into Muddy Creek, about 5 miles north of present-day Alderson. It was one of a series of forts built by militiamen to station troops and protect settlers from attack by native tribes who had caused them to abandon two earlier attempts at settling the area — one in the late 1750s and the other in the early 1760s. A third wave of settlers began arriving in, or returning to, the Greenbrier Valley in 1769.

“For the European settlers who lived here in the 1770s, this was the wild west,” said Gordon Campbell, president of the Greenbrier Historical Society, during a recent visit to the site.

Built on land claimed by John Keeney and family, who first arrived at the site in 1755, Arbuckle’s was one of the first frontier forts in the area to be built as a freestanding, military structure and not a fortified component of a home. In addition to building more substantial forts at sites with topography that enhanced their defense, the militia-built forts of the mid-1770s were spaced closer together than those built in previous decades. By the start of the Revolutionary War, forts in the Greenbrier Valley were sometimes built within 3 miles of each other.

The fort was built near the site of the July 1763 Muddy Creek Massacre, in which a raiding party led by Chief Cornstalk of the Shawnee killed three settlers and kidnapped a woman and three children.

Historic records indicate that Arbuckle’s Fort provided protection for many of the more than 40 families living in the Muddy Creek area at the time of its construction. During the growing season, families spent much of their time at the fort, with one group of male settlers moving from farm to farm, communally planting and harvesting crops, while another group was on alert for Indian attack.

The first military action at the fort took place in August 1774, within weeks of its completion, when Muddy Creek settler William Kelly was attacked by tomahawk-wielding Native American raiders about a half-mile outside the stockade. Sounds of the attack reached militiamen inside the fort, who ran to the scene and retrieved the deeply cut settler, who soon died of his wounds. The next day, American Indian raiders shot at a sentry standing watch at the fort, but missed their mark.

In September 1774, just after the fort was completed, Arbuckle and his troops guided Colonel Andrew Lewis and his force of nearly 1,000 Virginia militiamen to the Kanawha River, which they followed downstream to Point Pleasant.

From there, they planned to attack several native villages in Ohio as payback for raids on Virginia settlers. Instead, they encountered a like-sized force of warriors led by Chief Cornstalk, and the Battle of Point Pleasant ensued, ending in a narrow victory for the militiamen.

The only other record of Arbuckle’s Fort coming under attack took place in September 1777, when native raiders shot at the fort, but caused no casualties. It is believed that the raiding party was the same one that attacked a farmhouse at Lowell, about 20 miles to the north in Summers County, the previous day, killing three settlers and taking one prisoner.

The fort was occupied throughout much of the Revolutionary War, during which the British encouraged native attacks on the Virginia settlers, but 1783 was apparently the final year that the fort was garrisoned by militiamen.

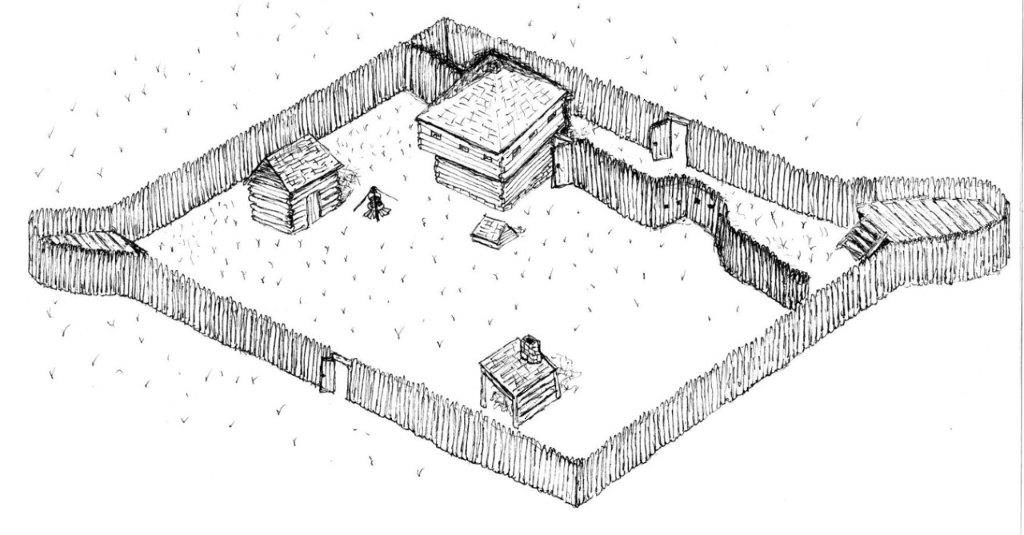

Excavations by the McBrides showed that a diamond-shaped stockade wall of vertical logs enclosed a quarter-acre area containing a blacksmithing site, cooking hearth, blockhouse and powder magazine. Bastions topped with observation decks were built at the north and south ends of the fort.

Artifacts uncovered during the excavations included a pair of dime-sized, eight-sided metal discs, one of which was engraved with an “X,” found in the blacksmith area. Similar discs have been found at a number of slave house sites across the South, and “suggest an African-American presence” at Arbuckle’s Fort, according to Kim McBride. “Tax records show that Matthew Arbuckle owned two slaves” at the time the fort was in use, she said.

A large quantity of assorted animal bones found in the cooking area indicated that meat formed a large portion of fort occupants’ diets. Hogs and cattle accounted for most of the bones, but deer, black bear, raccoon, rabbit, squirrel and groundhog bones were also found. An ethnobotanical study of samples of vegetable material found in the cooking area indicated that corn, fruits, nuts and berries were also consumed there.

A rifle sight, lead balls of various calibers, and gunflints of both domestic and European origin were among the defensive artifacts uncovered.

A small glass document seal that imprints the word “Liberty” was also unearthed, providing a tangible link between the militiamen who occupied the fort and the struggle for independence from Britain that was taking place when the fort was in use.

The seal would probably have been set in a ring or a cufflink, or something that could be worn on a chain or strap around the neck, according to McBride. The artifact “makes a wonderful link,” she said, to a 1776 letter Arbuckle sent to Col. William Fleming, a wounded veteran of the Battle of Point Pleasant, who was serving as a Virginia state senator when the letter was mailed.

“My country shall never have to say I dare not stand the attacks of the Indians,” or flee the cause his countrymen “are so justly fighting for,” Arbuckle wrote. “On the contrary, I will loose the last drop of my blood in defense of my country when fighting for that blessed enjoyment called liberty.”

The excavations at Arbuckle’s Fort also produced numerous artifacts left by the site’s earliest occupants, the region’s native people. Projectile points dating back to the Archaic era — 3,000 to 10,000 years ago — were found at the fort site and in the field surrounding it.

“In this little nook, 10,000 years of history can be found, “said Campbell. “We’re excited to be a part of it.”

The preserve will also encompass the remnants of a dam built to divert water for at least one of two gristmills that operated on Mill Creek. The first was Keeney’s Mill, in operation when the fort was built in 1774. It was replaced by Blaker’s Mill, built in 1794, which continued to operate well into the 20th century. It was moved to WVU’s Jackson’s Mill facility in the 1980s.

“Blaker’s Mill became the center of a small community that sprang up around it,” said Margaret Hambrick, secretary-treasurer of the Greenbrier Historical Society.

According to Hambrick, preliminary plans being considered for the preserve include building a small parking area, where signs will direct visitors where to see, and how to walk to, points of interest on the preserve. A path would follow Mill Creek past the Blaker’s Mill site and then ascend a gentle slope to the fort. Additional signage would be installed along along the trail.

While the preserve is not expected to draw vast crowds, “it adds another place for people to stop and see, and learn about the area’s history,” she said.

The Archaeological Conservancy, a national organization based in New Mexico, owns three other preserves in West Virginia, all them protecting the sites of prehistoric burial mounds. It previously owned another frontier fort site, Fort Evans in Hampshire County, that was later sold at cost to the Town of Capon Bridge.

“Our mission is broad,” said Ashton Berdine, lands program manager for the West Virginia Land Trust, better known for preserving natural areas, farms and forest tracts. “There are many places in West Virginia in need of protection. With Arbuckle’s Fort, we hope to provide public benefits for education and add economic value to the area.”

To donate to the effort to preserve Arbuckle’s Fort, visit https://give.archaeologicalconservancy.org/campaign/arbuckles-fort-archaeological-site/c289358. Each donation of $30 or more entitles the donor to a year’s membership in the Archaeological Conservancy, including a subscription to the quarterly magazine American Archaeology.

Toms Run Preserve is 318 acres located 10 minutes south of Morgantown. The West Virginia Land Trust has spent the last five years working hard to open this preserve to the public for hiking and nature study. We are sincerely thankful to all of our Blue Jean Ball supporters who supported this project! With the help of all of our grant funders, supporters, volunteers, staff and families, we are FINALLY ready to open this to the public! But in light of our current social distancing situation, we have to postpone our grand opening which was scheduled for April 2020. We hope to celebrate with you soon. Stay tuned for details on our celebration!

Signed, Sealed, Delivered… It’s Yours!

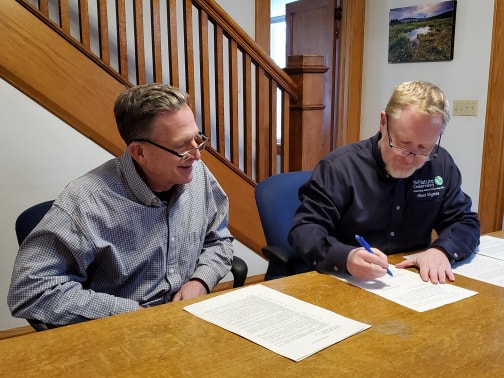

Last week, The Nature Conservancy in West Virginia (TNC) signed over the deed to a nearly 500-acre tract of land in Monroe County to West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT) for ownership.

Mike Powell, TNC director of lands, said this about the donation of land, “This property in Monroe County is special on many levels. However, it is outside our focus area and meant to be managed as a nature preserve. Therefore, we turned to our partners at the WVLT as the best stewards to manage this property and ensure the public can access it and enjoy it for years to come. It’s a win-win for us all and will result in a resilient, protected and publicly accessible piece of nature.”

The Nature Conservancy is a global environmental organization whose mission is to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. Here in West Virginia, the organization works to protect and restore the sweeping forests and wild rivers, to ensure West Virginia’s resources sustain both people and nature across the region for years to come.

Donated to TNC through an estate gift, the property is an important piece of an identified climate resilient networks of lands that connect the blue ridge to the boreal forests of Canada along the Appalachian Mountains. Conserving special places like this will benefit wildlife as the move to higher elevations, while also filtering air and water for people.

“The property has a forest of beautiful mature oak and white pine. The preserve also has interesting historic features, such as an old carriage trail lined with a massive stone wall, creating a ready-made hiking trail. This main trail is a leisurely hike for visitors and provides a wonderful place for nature lovers, birders and weekend hikers,” said Ashton Berdine, WVLT lands program manager.

West Virginia Land Trust plans to explore how this preserve can serve other community needs, such as recreational opportunities for mountain bike trails, but this would come much later after developing a management plan and working with local partners.

“We’d like to see a network of these kind of preserves all over the state, and we’ll achieve that with the support of people who love West Virginia and from conservation partners like The Nature Conservancy,” said Brent Bailey, WVLT executive director.

The West Virginia Land Trust is a statewide nonprofit dedicated to protecting special places, focusing on projects that protect scenic areas, historic sites, outdoor recreation and drinking water supplies by protecting land that borders rivers and streams.

Property Transferred to the City of Oak Hill

By: Steve Keenan/The Register-Herald

Continuously adapting, expanding and trying new approaches has become the norm for businesses which want to survive in today’s economy.

Municipalities can also be included in that list.

The City of Oak Hill cut the ribbon Tuesday on Needleseye Park, a rock climbing, hiking and mountain biking park on a large tract of land around the Minden area. The West Virginia Land Trust partnered with the city to purchase 283 acres of land from Berwind Land Co. for public recreational use.

West Virginia Tourism Commissioner Chelsea Ruby visited Fayette County for Tuesday’s ribbon-cutting, a fact which Oak Hill City Manager Bill Hannabass called “huge.”

While offering her thanks to the various entities involved in the process, Ruby thanked “most importantly, the community here, because you all have such a strong community when it comes to outdoor recreation, when it comes to tourism.”

When she attends events involving people in the region, Ruby said she knows there are going to be people who are passionate about tourism, growing the tourism economy, and outdoor recreation in the area.

“Day in and day out, you guys are the people who are on the ground.”

Ruby said Gov. Jim Justice’s administration has expanded the duties of the tourism office to include economic development, to look at ways to grow the state’s tourism economy.

“Everyone here knows how important tourism and outdoor recreation is to the state. I don’t have to tell you guys it’s a $4.3 billion industry in West Virginia. I don’t have to tell you that it brings in over $500 million in taxes. And I don’t have to tell you there’s 45,000 tourism jobs in West Virginia.

“Those are the reasons that we are all here today. It’s projects like this; it is growing the economy and adding new things to our list to promote.”

Outdoor recreation is consistently one of the main draws in the state, she said.

“When climbing really started to take off in the ‘80s here, people, of course, started off near the (New River Gorge) bridge,” recalled Gene Kistler, president of the New River Alliance of Climbers. “This place eventually got discovered here in the ’90s.

“We climbed here in the ’90s for maybe a couple of years, then maybe it was the Meadow River that everybody went to. It’s fun to discover things.”

“We knew about this place, and it’s just a brilliant move on the part of the City of Oak Hill to buy this and do this,” Kistler continued. “There’s a short list of cities in the U.S. that have climbing within the city limits, and it’s a prestigious list. And Oak Hill’s part of that now.

“What’s really nice about Needleseye is its exposure for winter climbing and for being here in the winter time. Frankly, summer time in Needleseye Park is kind of brutal. It’s going to be interesting to come up with ways to sort of mitigate that. But I think it’s gonna be primarily sort of a fall, winter, spring (best scenario).”

Kistler says the park offers a variety of options, including bouldering — “People are psyched.”

Brent Bailey, executive director of the West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT), said the fact that the project was locally-generated was a key.

“When we select projects, we’re looking for local buy-in,” Bailey said during a media hike before the ceremony. “This was an easy buy for us.”

According to Bailey, the WVLT seeks to get involved with projects that will provide public benefit such as protecting water supply, providing recreation and preserving history.

After exploring the title on the land and other areas such as mineral issues and boundaries, the WVLT wrote a proposal to move the project along. Needleseye features “beautiful West Virginia woodland and spectacular rock formations,” he said.

Hannabass termed Tuesday “a fantastic day for the City of Oak Hill.” Initiated in March 2016, the Needleseye project “moved at lightning speed,” he said.

Mayor Fred Dickinson and city council threw their support behind the project, and the WVLT and the state’s Outdoor Heritage Conservation Fund came on board, as did other partners.

“You have to have multiple partners. You can’t do this as one entity,” the city manager said.

“I found very quickly that this property speaks for itself,” Hannabass said during the media hike. “It should be public, it should be protected, it should be for the enjoyment for all of us for generations and generations and generations to come, and it is, and that’s why we’re here to cut the ribbon.”

He said the project cost has been around $600,000, with the city and the WVLT contributing some funds, but the bulk of the money coming from the Outdoor Heritage Conservation Fund in the form of a grant to purchase the property from Berwind.

“Outdoor recreation is extremely important to our state,” said Jessica Spatafore, WVLT’s director of development and communications. “In addition to benefiting our current local residents and their health, outdoor rec opportunities strengthen our economy by increasing tourism, attracting new businesses and boosting the housing market.”

With the parking lot and access now available at the north entrance, other future work includes signage and creation of a south entrance, said Hannabass.

“There will be some more amenities to come,” as well as promotion of the park, he said.

To access the north entrance parking lot, turn on Gatewood Road from Main Street Oak Hill, travel 1.6 miles, turn right on Needleseye Road and go 0.5 of a mile to the parking lot.

……………………………………………………………………

Original story: https://www.register-herald.com/oak-hill-christens-needleseye-park/article_228dfa8a-7c3b-11e9-a1b7-cf2dc0ad5d19.html?fbclid=IwAR2xj1lHspZtohNpXUFY2Dh77jJo_hojfGXtloeeKMWWf46TSxhxgmFekXk

West Virginia Land Trust Celebrates Earth Day with the Help of Local Volunteers

In celebration of Earth Day, the West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT) welcomed nearly twenty employee volunteers from MedExpress Urgent Care to help build new hiking trails in two WVLT-owned nature preserves.

“Outdoor recreation is extremely important to our community,” said Jessica Spatafore, WLVT director of development and communications. “In addition to benefitting our current local residents and their health, outdoor rec opportunities strengthen our economy by increasing tourism, attracting new businesses, and boosting the housing market.”

MedExpress center volunteers from Morgantown worked in the Toms Run Nature Preserve, which is a 320-acre natural area. The property is a “work in progress” and WVLT is planning to make it open and accessible to the public for hiking and nature study in the fall of 2019.

Volunteers from the Charleston MedExpress center met in the Wallace Hartman Nature Preserve. This 52-acre natural area has established trails and is open to the public. The preserve offers recreational and educational opportunities, habitat protection and scenic enjoyment.

MedExpress employees were able to volunteer with the WVLT through the MedExpress Volunteer Program in which team members can take a certain amount of time off to volunteer in their community with an organization of their choice.

Those interested in visiting either property or volunteering should call WVLT at (304) 413-0945.

(Pictured above: Ted Armbrecht, WVLT Board of Directors; Brent Bailey, WVLT Executive Director; Ashton Berdine, WVLT Lands Program Manager; Larry Harris, WVLT Board of Directors)

Morgantown, WV – Monday, December 10 at the Courtyard by Marriott, Governor Jim Justice announced more than a dozen grants awarded to recipients in Northern West Virginia. These included two Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Grants, six Recycling Assistance Grants, and 11 Recreational Trails Program Grants.

“These grants are essential as we continue to grow West Virginia and provide programs that help our communities and citizens,” Gov. Justice said. “The multiplier effect on our return is at least eight times and many times it is more. As we move our state forward, and we are, the impact to our economy is substantial.”

The winter storm that affected Southern West Virginia prevented the Governor from attending the press conference. Bray Carey, Special Assistant to the Governor, attended on his behalf. Ed Maguire of the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, which administers the AML program, announced the awards.

The West Virginia Land Trust was awarded a $400,000 AML grant to contribute towards the purchase and restoration of approximately 900 acres in Tucker County that include highly popular recreational trails that have become a regional destination for hiking and mountain biking. Upon purchase, the property will be called Yellow Creek Preserve, named after a tributary of the Blackwater River that flows through the property. The property also includes Moon Rocks, a rock formation that is a popular destination for hikers and mountain bikers.

“This group has already been fundraising and invested some of their own money into this campaign to purchase the property,” said Ed Maguire, Director of the office of the Environmental Advocate for the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. “That impressed us on the selection committee because this group put a lot of their own skin in the game,” Maguire said.

During the award presentation, Maguire recalled hiking the property and indicated that the property is a cornerstone for the recreation in the Canaan Valley area, which depends on tourism as an important part of its economy.

“This is an important piece of property that draws people to nearby communities and that we intend to make available to the public for recreation,” said Brent Bailey, West Virginia Land Trust Executive Director.

According to the land trust, the property is threatened by development, so they stepped in to see it protected.

“In recent years, parts of the property were being sold parcel by parcel into private ownership and that threatened public access,” Bailey said.

At the award ceremony, Maguire indicated that although the property sits in an area with abandoned mine lands, it still has significant recreational and conservation values. The property borders nearly 20,000 acres of other public lands that include the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Little Canaan Wildlife Management Area.

“It not only has tremendous recreation potential, it also includes unique upland and wetland habitats that create the iconic landscapes that draw people to the Canaan Valley area,” Bailey said.

To learn more about the project, visit www.BuyTheMoonWV.org or call (304) 413-0945.

(Click here for the article)

by: Charleston Gazette-Mail

Join us for a Celebration of Needleseye Boulder Park!

Together, the West Virginia Land Trust and City of Oak Hill will host a community open house to celebrate the opening of Needleseye Boulder Park on May 19 from 12:00-4:00 PM. The celebration will take place in The Lost Paddle restaurant at ACE Adventure Resort, with ACE offering shuttles to the Needleseye Park trailhead every 30 minutes for guided hikes.

“Saving the world one sip at a time…” (Click here to view article)

by: The Daily Athenaeum