Effort underway to preserve Revolutionary War-era fort site in Greenbrier County

Charleston Gazette-Mail

By Rick Steelhammer

Jul 11, 2020

ALDERSON — A crowdfunding campaign is underway to protect the site of one of the strongest in a series of frontier forts built to protect colonial settlers in the Greenbrier Valley from raids by American Indians before and during the Revolutionary War.

The Archaeological Conservancy, the West Virginia Land Trust and the Greenbrier Historical Society are seeking to raise $125,000 — $60,000 of it from the crowdsourcing effort — to buy the fort site and a 25-acre parcel of land surrounding it. The three groups would then work together to create a public historical preserve, with signs, trails and exhibits pointing out the cultural and natural points of interest being protected from development.

The Outdoor Heritage Conservation Fund has committed $25,000 to manage the preserve.

While the location of the fort was known, no written description of it is known to exist, and no trace of the fortification could be seen above the surface of the pasture that covers it. Much of what is known about the structure and the activities that took place inside it was uncovered during a series of excavations conducted in the 1990s by archaeologists Stephen and Kim McBride.

The McBrides, both Greenbrier County natives with doctorates in archaeology, were assisted by students from public schools in Greenbrier County, students from the University of Kentucky, Concord and West Virginia University, and local volunteers.

Arbuckle’s Fort was built in 1774 by a local militia company commanded by Captain Matthew Arbuckle on a knoll overlooking the point where Mill Creek flows into Muddy Creek, about 5 miles north of present-day Alderson. It was one of a series of forts built by militiamen to station troops and protect settlers from attack by native tribes who had caused them to abandon two earlier attempts at settling the area — one in the late 1750s and the other in the early 1760s. A third wave of settlers began arriving in, or returning to, the Greenbrier Valley in 1769.

“For the European settlers who lived here in the 1770s, this was the wild west,” said Gordon Campbell, president of the Greenbrier Historical Society, during a recent visit to the site.

Built on land claimed by John Keeney and family, who first arrived at the site in 1755, Arbuckle’s was one of the first frontier forts in the area to be built as a freestanding, military structure and not a fortified component of a home. In addition to building more substantial forts at sites with topography that enhanced their defense, the militia-built forts of the mid-1770s were spaced closer together than those built in previous decades. By the start of the Revolutionary War, forts in the Greenbrier Valley were sometimes built within 3 miles of each other.

The fort was built near the site of the July 1763 Muddy Creek Massacre, in which a raiding party led by Chief Cornstalk of the Shawnee killed three settlers and kidnapped a woman and three children.

Historic records indicate that Arbuckle’s Fort provided protection for many of the more than 40 families living in the Muddy Creek area at the time of its construction. During the growing season, families spent much of their time at the fort, with one group of male settlers moving from farm to farm, communally planting and harvesting crops, while another group was on alert for Indian attack.

The first military action at the fort took place in August 1774, within weeks of its completion, when Muddy Creek settler William Kelly was attacked by tomahawk-wielding Native American raiders about a half-mile outside the stockade. Sounds of the attack reached militiamen inside the fort, who ran to the scene and retrieved the deeply cut settler, who soon died of his wounds. The next day, American Indian raiders shot at a sentry standing watch at the fort, but missed their mark.

In September 1774, just after the fort was completed, Arbuckle and his troops guided Colonel Andrew Lewis and his force of nearly 1,000 Virginia militiamen to the Kanawha River, which they followed downstream to Point Pleasant.

From there, they planned to attack several native villages in Ohio as payback for raids on Virginia settlers. Instead, they encountered a like-sized force of warriors led by Chief Cornstalk, and the Battle of Point Pleasant ensued, ending in a narrow victory for the militiamen.

The only other record of Arbuckle’s Fort coming under attack took place in September 1777, when native raiders shot at the fort, but caused no casualties. It is believed that the raiding party was the same one that attacked a farmhouse at Lowell, about 20 miles to the north in Summers County, the previous day, killing three settlers and taking one prisoner.

The fort was occupied throughout much of the Revolutionary War, during which the British encouraged native attacks on the Virginia settlers, but 1783 was apparently the final year that the fort was garrisoned by militiamen.

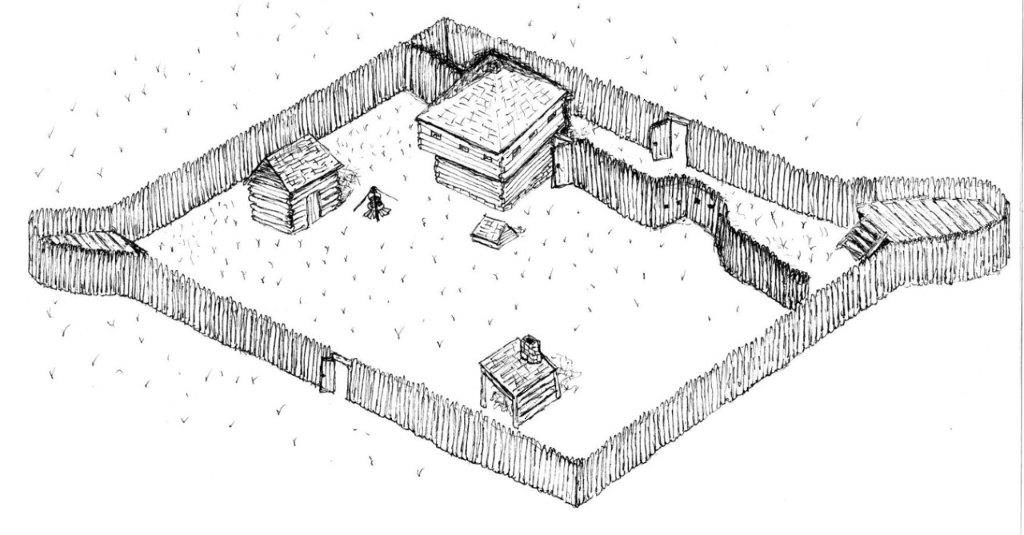

Excavations by the McBrides showed that a diamond-shaped stockade wall of vertical logs enclosed a quarter-acre area containing a blacksmithing site, cooking hearth, blockhouse and powder magazine. Bastions topped with observation decks were built at the north and south ends of the fort.

Artifacts uncovered during the excavations included a pair of dime-sized, eight-sided metal discs, one of which was engraved with an “X,” found in the blacksmith area. Similar discs have been found at a number of slave house sites across the South, and “suggest an African-American presence” at Arbuckle’s Fort, according to Kim McBride. “Tax records show that Matthew Arbuckle owned two slaves” at the time the fort was in use, she said.

A large quantity of assorted animal bones found in the cooking area indicated that meat formed a large portion of fort occupants’ diets. Hogs and cattle accounted for most of the bones, but deer, black bear, raccoon, rabbit, squirrel and groundhog bones were also found. An ethnobotanical study of samples of vegetable material found in the cooking area indicated that corn, fruits, nuts and berries were also consumed there.

A rifle sight, lead balls of various calibers, and gunflints of both domestic and European origin were among the defensive artifacts uncovered.

A small glass document seal that imprints the word “Liberty” was also unearthed, providing a tangible link between the militiamen who occupied the fort and the struggle for independence from Britain that was taking place when the fort was in use.

The seal would probably have been set in a ring or a cufflink, or something that could be worn on a chain or strap around the neck, according to McBride. The artifact “makes a wonderful link,” she said, to a 1776 letter Arbuckle sent to Col. William Fleming, a wounded veteran of the Battle of Point Pleasant, who was serving as a Virginia state senator when the letter was mailed.

“My country shall never have to say I dare not stand the attacks of the Indians,” or flee the cause his countrymen “are so justly fighting for,” Arbuckle wrote. “On the contrary, I will loose the last drop of my blood in defense of my country when fighting for that blessed enjoyment called liberty.”

The excavations at Arbuckle’s Fort also produced numerous artifacts left by the site’s earliest occupants, the region’s native people. Projectile points dating back to the Archaic era — 3,000 to 10,000 years ago — were found at the fort site and in the field surrounding it.

“In this little nook, 10,000 years of history can be found, “said Campbell. “We’re excited to be a part of it.”

The preserve will also encompass the remnants of a dam built to divert water for at least one of two gristmills that operated on Mill Creek. The first was Keeney’s Mill, in operation when the fort was built in 1774. It was replaced by Blaker’s Mill, built in 1794, which continued to operate well into the 20th century. It was moved to WVU’s Jackson’s Mill facility in the 1980s.

“Blaker’s Mill became the center of a small community that sprang up around it,” said Margaret Hambrick, secretary-treasurer of the Greenbrier Historical Society.

According to Hambrick, preliminary plans being considered for the preserve include building a small parking area, where signs will direct visitors where to see, and how to walk to, points of interest on the preserve. A path would follow Mill Creek past the Blaker’s Mill site and then ascend a gentle slope to the fort. Additional signage would be installed along along the trail.

While the preserve is not expected to draw vast crowds, “it adds another place for people to stop and see, and learn about the area’s history,” she said.

The Archaeological Conservancy, a national organization based in New Mexico, owns three other preserves in West Virginia, all them protecting the sites of prehistoric burial mounds. It previously owned another frontier fort site, Fort Evans in Hampshire County, that was later sold at cost to the Town of Capon Bridge.

“Our mission is broad,” said Ashton Berdine, lands program manager for the West Virginia Land Trust, better known for preserving natural areas, farms and forest tracts. “There are many places in West Virginia in need of protection. With Arbuckle’s Fort, we hope to provide public benefits for education and add economic value to the area.”

To donate to the effort to preserve Arbuckle’s Fort, visit https://give.archaeologicalconservancy.org/campaign/arbuckles-fort-archaeological-site/c289358. Each donation of $30 or more entitles the donor to a year’s membership in the Archaeological Conservancy, including a subscription to the quarterly magazine American Archaeology.