Story by Rick Steelhammer at Charleston Gazette-Mail.

The West Virginia Land Trust has assumed management of a historic Monroe County cave system.

The cave was once mined for saltpeter by pioneer settlers and Confederate soldiers. Saltpeter is a key component in the making of gunpowder. The cave now provides habitat for at least two endangered bat species.

Partial funding for the preserve was made available as habitat impact mitigation arising from construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which passes just west of Greenville.

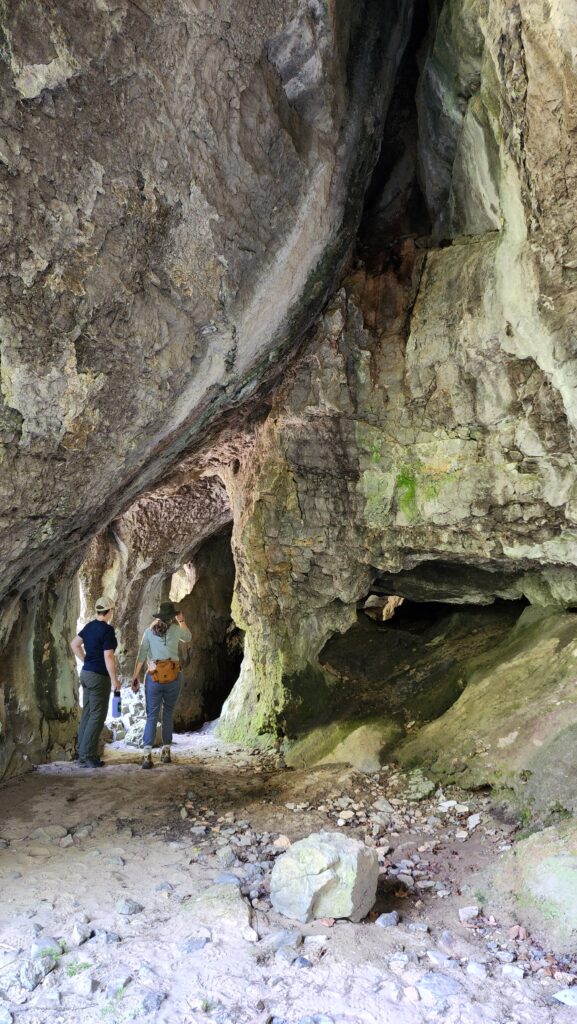

The new, 298-acre Greenville Saltpeter Cave Preserve encompasses its namesake limestone cavern, which contains nearly 4 miles of mapped passages.

Prime habitat for bats

The cave provides prime habitat for endangered Indiana and Northern long-eared bats during their breeding and hibernation seasons, which extend from late summer to early spring. The cave also shelters one of the largest surviving populations of the tricolored bat, which is under review for Endangered Species Act protection.

The preserve, to be managed in cooperation with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, will be the first site in the Mountain State where a promising experimental treatment designed to reduce bats’ vulnerability to white-nose syndrome will be deployed. A fungal disease that has brought about precipitous declines in bat populations since it appeared in the United States in 2006, white-nose syndrome disrupts hibernation, causing dehydration, starvation and often death.

DNR biologists will bathe in ultraviolet light the ceilings and walls where hibernating bats congregate in large numbers in Greenville Saltpeter Cave. The UV light is a wavelength capable of neutralizing the pathogen that causes the disease. The UV-C light has a minimal effect on other cave-dwelling organisms, and after it is applied, leaves no trace residue within the cave.

“UV-C light treatment is a cutting-edge process,” said Alex Silvis, the DNR biologist who led the white-nose syndrome treatment project. “I am enthusiastic the results will be positive and the UV-C light method will become standard practice in reducing white-nose syndrome.”

Acquisition process, and history of the caves

The preserve was acquired by The Conservation Fund, a national nonprofit involved with land and water protection. The DNR asked the organization to negotiate with the tract’s two private landowners, with the understanding that the land would become a cave preserve. Ownership of the land was then transferred to the West Virginia Land Trust.

“The biological and historical value of this land made it clear to everyone involved that permanent conservation was more than just prudent — it was paramount,” said Joe Hankins of Shepherdstown, vice president of The Conservation Fund, as well as the organization’s state director.

“Our partners at West Virginia Land Trust will serve as unparalleled caretakers for this land,” Hankins said. “We’re thrilled to have helped secure this outcome, which will benefit West Virginians for decades to come.”

The nonprofit Institute for Earth Education, which owned half of the land that makes up the new preserve and had begun a conservation stewardship program for the cave system, will partner with the Land Trust on educational and interpretive programs at the preserve.

“These caves have long held a special place in the hearts of those living in Monroe County and beyond,” said Amanda Sandell, who owned the other half of the preserve’s acreage. “May this protection serve to preserve the caves for generations to come.”

From 1777 until the start of the Civil War, the Greenville Saltpeter Cave was mined extensively for saltpeter, a key ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder. During the Civil War, the cave was mined to help keep the Confederate army supplied with gunpowder.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, one entrance to the cavern, known as the Singing Cave, was used by church groups for gospel sings, because of its favorable acoustics.

In his 1958 book, “Caverns of West Virginia,” geologist William Davies William wrote that “cart ruts, burro tracks, mattock marks and other relics of saltpeter operations” could be found inside the Greenville Saltpeter Cave. However, many of those remnants have since been removed, damaged or destroyed by vandals, according to the Land Trust.

Public access to the preserve

The previous owners of the preserve’s property, following recommendations by the DNR and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, installed gates at the cave’s five entrances to restrict human access in an effort to prevent the spread of white-nose syndrome.

While the cave is expected to remain closed to the public for a number of years, the surface portion of the preserve may be open for public hiking, bird-watching, nature study and photography after the DNR’s UV-C project is completed.

The Land Trust will work with the DNR, Fish and Wildlife and the Institute for Earth Education on a plan to safely open the property to the public, according to a release from the Land Trust.

Funding for new preserve was made possible through a voluntary stewardship agreement between the DNR, the West Virginia Land Trust, The Conservation Fund and Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC. The agreement provided funds to buy and manage land for the preserve and fund the West Virginia DNR’s bat research project in the cave.

Story by Rick Steelhammer at Charleston Gazette-Mail: https://www.wvgazettemail.com/outdoors/recreation/wv-land-trust-to-preserve-manage-historic-monroe-county-cave/article_9ecc7ec4-109f-581e-bbea-5a13b2ad9b2a.html